RBGPF

0.1600

A bitterly-fought climate finance deal reached at COP29 risks weakening emissions-cutting plans from developing countries, observers say, further raising the stakes for new national commitments due early next year.

The UN climate talks in Azerbaijan, which concluded last Sunday, were considered crucial to boosting climate action across huge swathes of the world after what will almost certainly be the hottest year on record.

Beginning days after the re-election of climate sceptic Donald Trump as US president, and with countries weighed down by economic concerns, the negotiations were tough-fought from the start and at one point seemed close to collapse.

Wealthy polluters ultimately agreed to find at least $300 billion a year by 2035 to help poorer nations transition to cleaner energy and prepare for increasing climate impacts such as extreme weather.

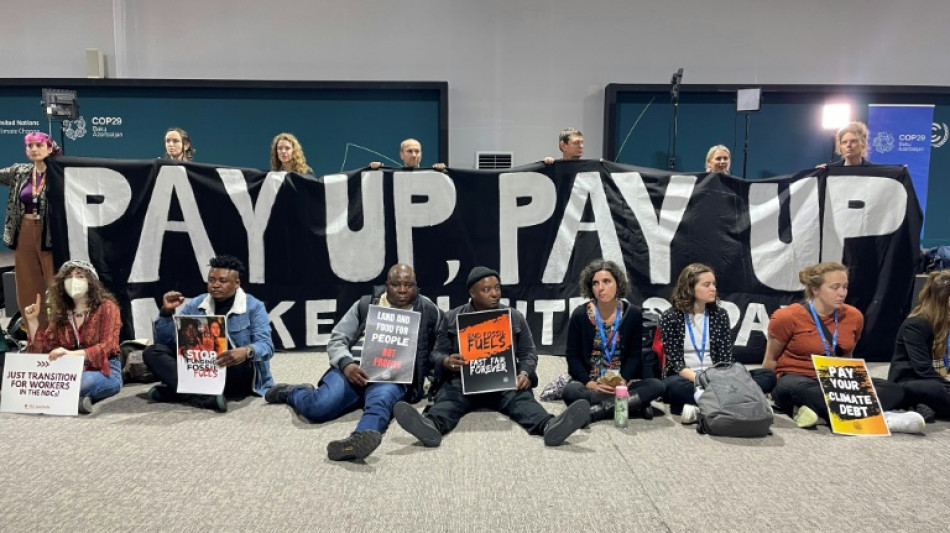

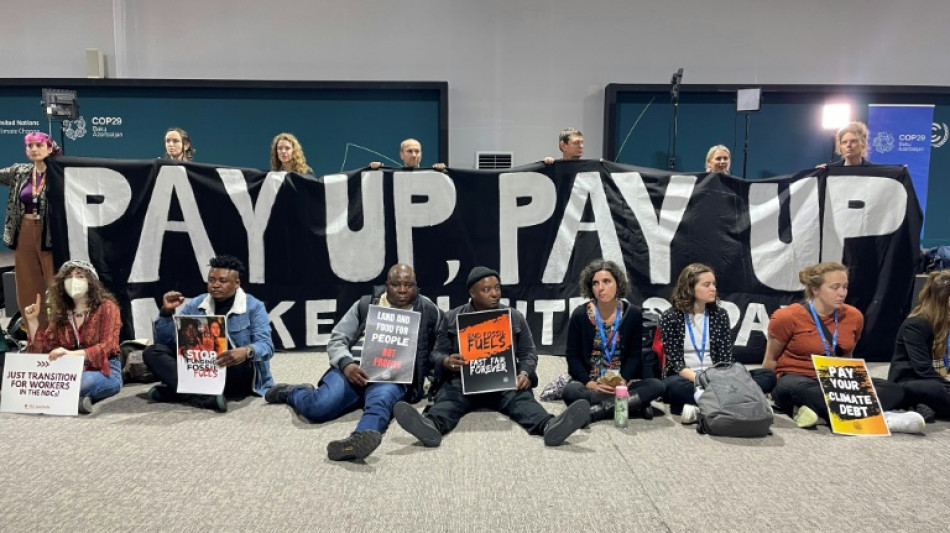

But it was slammed by developing nations as too little, too late.

Taking the floor just after the deal was approved, Nigeria's representative Nkiruka Maduekwe dismissed the funding on offer as a "joke", suggesting it would undermine national climate plans due early next year.

"$300 billion is unrealistic," she said. "Let us tell ourselves the truth."

Current climate plans, even if implemented in full, would see the world warm a devastating 2.6 degrees Celsius this century, the United Nations has said, blasting past the internationally agreed limit of 1.5C since the pre-industrial era.

A next round of national pledges is due in February and will cover the period to 2035, which scientists say is critical for curbing warming.

Mohamed Adow of Power Shift Africa, a Kenya-based think tank, said the COP29 talks produced not just a "low-ball" figure, but a delivery date of 2035 that falls at the end of the range for climate plans.

This "will certainly constrain the ability of developing countries to pledge ambitious emission cuts", he told AFP, calling for an improved goal and other measures, like debt relief and technology support.

- 'Our only chance' -

Global emissions need to be reducing by more than seven percent every year "to avoid unmanageable global outcomes as the world breaches the 1.5C limit", said Johan Rockstrom of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

"Our only chance is full focus on financing and implementing emission cuts now."

Yet carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels -- the main driver of global warming -- are still rising, according to the Global Carbon Project.

The COP29 deal acknowledged that lower income countries will need some $1.3 trillion annually to pay for their energy transition and build up their resilience to future climate impacts.

Details of how to bridge the $1 trillion funding gap remain vague, but it would likely require a major effort to attract money from private investors, development banks and other sources.

Other ideas include raising money through pollution tariffs, a wealth tax or ending fossil fuel subsidies.

Friederike Roder of campaign group Global Citizen said discontent over COP29 piles pressure on countries to come up with concrete suggestions before the next climate meeting in Brazil in November 2025.

That would "help rebuild some of the trust and give confidence to countries to come forward with ambitious targets", she told AFP.

- EU-China 'momentum' -

So far only a handful of countries -- recent and future COP hosts Britain, the UAE and Brazil -- have unveiled new climate plans.

Observers say many other nations are now unlikely to meet the February deadline, as governments grapple with shifting political and economic situations.

The new year will see a new Trump administration in the White House, with potentially sweeping implications for international trade and US climate policy.

Germany, Canada and Australia will all hold elections in which conservatives less supportive of green policies stand a chance of victory.

With the United States retreating from climate diplomacy, the relationship between China and the EU will likely become "the best source of momentum" on climate, said Li Shuo, director of the China climate hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute.

One positive takeaway from COP29, he added, was early evidence of a willingness to work together, despite the trade rivalry between Beijing and Brussels.

A lack of progress on emissions at COP29 has also caused alarm over stalling efforts on curbing warming.

But Catherine Abreu, director of the International Climate Politics Hub, said the rejection of a watered down text on the subject this year meant national climate plans should still reflect last year's COP28 pledge to move away from planet-heating fossil fuels.

It is small consolation.

"Here we are in the hottest year on record. The impacts are enormous," she said.

S.Yamamoto--JT